Originally published on 7/4/2023

American Independence Day seems like as good a day as any to write about the confounding reality of trying to make money selling art.

A big motivator in my life has been my desire to be free from the constraints that typically come with a so-called regular job. Part of the reason I’ve always been a mediocre employee is because I always thought I’d make money by making art, although all through art school and beyond, I wasn’t too clear on what that would look like. I think I just thought it would magically happen. As if my art were so wonderful, so desirable, that buyers would be busting down my door to get it.

That has not been my experience, so far. But I’m not dead yet. It could still happen, I suppose. I’m not the boss of the future. However, I’m older now, and less idealistic about becoming a successful artist. I’m not even sure what that means. Some days, the fact that I’m still standing seems like a success.

What is success?

Defining success for an artist requires a tiptoe through a minefield of values and expectations. What does success mean to you? And what are you willing to do, how much are you willing to compromise, to get it?

Will you “adapt” your artistic integrity to get money? How much are you willing to adapt your art to fulfill someone else’s vision?

You can tell I have a chip on my shoulder about this topic by the way I frame my questions. I have long had a reluctance to let other people tell me what to make and how to make it. It’s all or nothing in my world. I’m either making your art or I’m making mine—for me, there is no middle ground.

Some of you either purposefully or accidentally find that lovely intersection between making what you want to make and making what the market wants to buy. It’s a wonderful thing when that happens, like finding the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. I envy you, if you are one of those lucky creators. The middle ground can keep you fed and sheltered for the rest of your life.

In my mentoring, I encounter a few creatives who have found this happy place. I also meet people who are as unwilling to compromise as I am. We commiserate a little, but not for long. They come to me for guidance. It does no good to spend the session complaining about how much we hate to compromise when there’s a stack of paintings in the attic and the artist needs to pay the rent.

First, we need to define success. What does success mean for you? Be specific. Generate enough income to pay the bills? Earn enough to buy an island in the Caribbean? Figure out the dollar amount you want. If you don’t know the goal, it’s impossible to make a plan to get you there. So, figure out your goal.

Commit to one art form

We can’t sell all things to all people and call that an art business. There’s no way to differentiate the business in the marketplace. Choose a niche and focus on it for at least six months. Do all the business-y things you need to do to be legal. Squat on that domain name. Start building a presence in the online market space. Get over your reluctance to be visible.

Committing to one art form doesn’t mean you can’t pursue all those other cool things you do, just don’t declare on your website that you make pottery and crocheted hats when you are trying to develop a business as an illustrator of children’s books.

Choose your pricing model

It doesn’t matter how you choose to set your prices. Just be consistent. You can price by the square inch or the cubic foot. You can add up your costs and tack on extra for overhead and profit margin. You can set your income goal and divide by the number of pieces you can make and sell in a month. It doesn’t matter what model or combination of approaches you use, just strip out the emotion, and be consistent.

Identify your target market

Not everyone cares about art. Not everyone will care about your art. However, I guarantee you, there is a segment of the buying public who would love to buy what you make, if only they knew about it. Can you guess who they might be? Think about demographics (age, gender, income level, geographic location, etc.), but also think about psychographics (what benefits do they seek, what problems do they have that need to be solved?) If you know what motivates them, then you will have a better idea of how to message them.

Reach out to your potential buyers

Reaching out means, yes, you might need an onine presence, including a website and social media accounts. For some of you, though, reaching out can mean literally communicating with your potential buyers where they are.

For example, if you make art that interior designers might like to buy or commission, you know where to find them. They have websites. They have offices in your city. They are on LinkedIn. It’s plain old direct sales, and it’s all about relationships. Consider this: a handful of interior designers calling you a few times a year for commissions could keep you going for the rest of your life.

Don’t fall into the trap of believing that once you launch a website and set up some social media accounts, your work is done. That’s like building your store five miles off the main highway up a dirt road with no signage and expecting customers to somehow find you. It’s not going to happen.

Don’t expect a few social media posts to do your promotion for you. We don’t control what eyeballs see our posts. Where are the members of your target market? You want to be where they are. They might not be on social media at all.

Aim high, begin low, climb slowly, and don’t give up

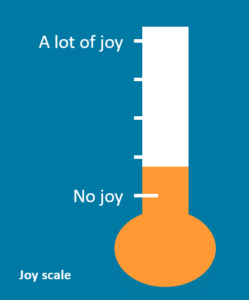

Consider how much joy chasing money with your art will bring you. You may decide after all this folderol that it’s not worth it. Trying to turn your art into a business might cause your Joy Scale to drop into negative territory.

What is the Joy Scale?

Glad you asked. On a scale of 1 to 10, how much joy does the idea of trying to turn your chosen art form into a moneymaker generate for you? If it’s less than a 5 on the Joy Scale, I encourage you to rethink your path. For some us, me included, having a day job is the lesser of two soul-wrenching, creativity-killing evils.

If you can’t find the happy intersection between art and money, make the art you love, without expectation of return or reward. Don’t quit. Miracles could happen. You might be one of those mythical creatures I’ve heard about.